A series of exhibitions from curator Vali Mahlouji examine the ‘lost decades’ of pre-revolutionary Iran

|

| Polaroids by Kaveh Golestan Photograph: Kaveh Golestan/Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

Polaroids by Kaveh Golestan

A lizard-headed strongman and a nineteenth-century noblewoman pose together on a chaise lounge. Outstretched before a crowd of Qajar dignitaries lies a nude woman. A monstrous birdman clutches a bunch of bloodied and shrivelled heads, which dangle from his fist like a cluster of screaming mandrakes.Such are the surreal and provocative scenes in the sepia-hued Polaroids by Iranian photographer Kaveh Golestan, who entitled these collages Az Div o Dad (Of Beast and Wild, quoted from the classical Persian poetry of Rumi). Golestan – a figure who lived and died by his photojournalism, killed in 2003 while documenting the Iraq war for the BBC - created this innovative series in 1976 by moving collaged fragments in front of an open shutter under long exposure. The images are experimental visions of modern and later Qajar-era (c.1844-1925) photography spliced with the tails and heads of wild animals and the curved flesh of nude figures.

These images are just some of the artistically radical - and temporally pre-revolutionary – materials recently recovered from Iran’s “lost decades”, rarely glimpsed or even known by those both inside and outside the country itself. This spring, three exhibitions reveal the photographic evidence of Iran’s largely forgotten cultural climate of the 1960s and 70s to audiences in London and the UAE. The first show takes place this March, as Golestan’s Az Div o Dad Polaroids are unveiled at Art Dubai, and will expand on the exposure of Kaveh Golestan’s diverse oeuvre. It is a significant moment to premiere these photographs, which have been unseen for over forty years since Golestan first debuted his surrealistic series at the Seyhoun Gallery in Tehran.

|

| Polaroids by Kaveh Golestan Photograph: Kaveh Golestan/Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

Golestan’s Polaroids form a new strand of the project Archeology of the Final Decade, the brainchild of London-based curator Vali Mahlouji. This archive and research platform aims to re-compile segments of Iranian cultural life in the pre-revolutionary moment before 1979, where the original material has been either removed from circulation, remains under-exposed, or placed under lock and key. Golestan’s photographs are just some of the unique discoveries that have emerged from Mahlouji’s digging, and they, along with other endangered or forgotten material from the 1960s and ‘70s, are being edited back into Iranian reality through a series of international exhibitions.

|

| Polaroids by Kaveh Golestan Photograph: Kaveh Golestan/Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

Originally trained as an archaeologist, Mahlouji now unearths photographs and documents as the skeletons of Iran’s unresolved cultural past. “The project works in two dimensions, which its name reflects” he explains from his London archive. “Firstly, the downward delving into the past, [which is] akin to archaeological practice. After diving vertically across a timescale into the origins of these things, you work horizontally into the context of the material.” His efforts unearth pertinent, and sometimes uncomfortable, issues of memory, history and reintegration. Mahlouji aims to raise awareness of these materials and revisit the events from which they emanated, which were often controversial in their own time.

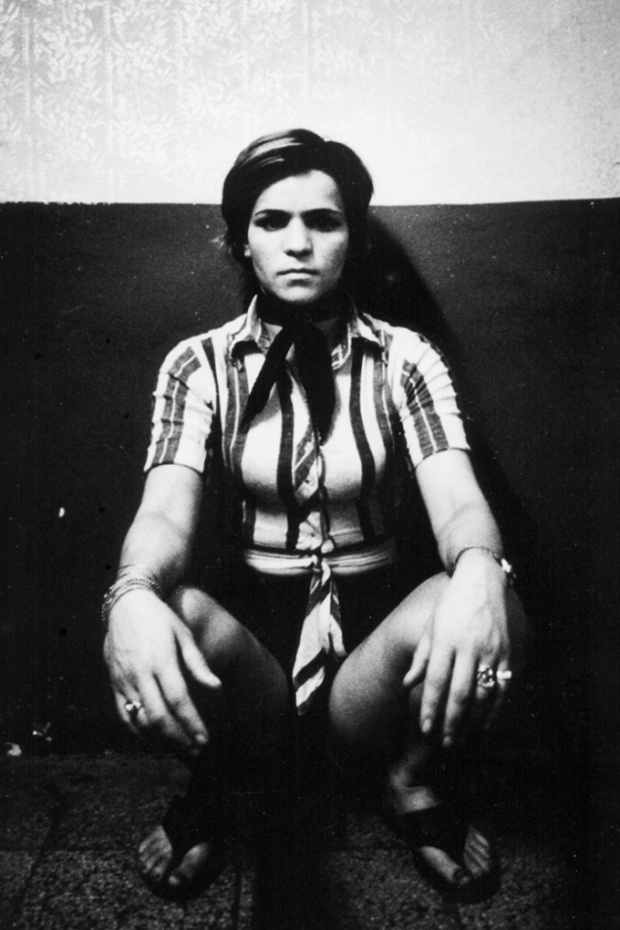

‘Prostitute’

The first two phases of the project shed light on Golestan’s photographs and videos of 1970s prostitutes from Tehran’s now obsolete red light district Shahr-e No (New City) and delved into the extant memorabilia from the Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of the Arts, a pioneering international arts event which took place across both Iranian cities from 1967 to 1977. This initial iteration of Archaeology of the Final Decade, centering on the artistic and intellectual milieu of the final decade before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, was previously exhibited in its own dedicated show space within the recent Iran: Unedited History 1960-2014. Prior to that, for the first time since 1978, Golestan’s “Prostitute” photographs were exhibited at the Foam Photography Museum in Amsterdam in March 2014. |

| Kaveh Golestan ‘Prostitute’ series Photograph: Kaveh Golestan/Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

For Archaeology of the Final Decade to show at Art Dubai is in itself a novelty, by introducing a non-profit project within an event that is a frenetic hub of international monetary exchange around art. The Polaroids have been allocated a non-commercial exhibition space within the fair’s Dubai Modern section. It is also a first for the Middle East, as Mahlouji points out: “Can you think of another Middle Eastern artist who used Polaroid as a medium?” It is indeed a rogue choice of format for a photojournalist, but is also unmatched by any other Iranian artist. And that medium itself is quickly becoming obsolete as Polaroid ceased film production in 2008, making these photographs even more of a treasure in a body of work which already holds the weight of Iran’s forgotten decades.

The new station at Art Dubai is also symptomatic of an increasing interest in Golestan from the global art world since Mahlouji began exposing the works. Mahlouji speculates that there is perhaps a wish by gallerists to claim Golestan posthumously away from his long held status as a photojournalist, and these fantasy collages provide a compelling case of departure from his stark documentary work. Indeed, in creating these hybrid Polaroids, Golestan was working very self-consciously as an artist, in a manner very different to the unflinching investigative style in which he captured life in the citadel of Shahr-e No in his Prostitute series of 1975-77, the years that bracket this experimental flourish.

With his Polaroid images, Golestan had condensed his new surrealist vision into the dimensions of Type 600 film. However makeshift and small, the images are intensely compelling: quixotic flights of fancy from the hands of a man who gave his life to a self-confessed mission of uncovering what he termed the “unstoppable truth” in his documentary photographs. Despite Art Dubai’s reputation as an international art platform, showing the Polaroids there was not without its own controversy. Any image showing nudity was unable to be exhibited. As many of the Az Div o Dad images feature nudes, perhaps areas of the Middle East’s commercial art world so eager to claim Golestan are not as ready for his vision as they had anticipated. And so, Golestan remains a fascinating figure, straddling the realms of the professional and the provocative in his public work as a photojournalist and his personal experiments as an artist.

There is also an opportunity to view Golestan’s more sobering, but equally pioneering, documentary photography of Tehran’s underbelly in London this May. Mahlouji looks through a slideshow of the history of the citadel of Shahr-e No and the black and white originals of Golestan’s Prostitute series that will be on show at the Photo London Fair. He stops at an early photograph before the erection of the citadel wall in 1953, a structure that simultaneously confined and defined the area as an inner-city ghetto. The photograph shows two women, one topless, having a chat over cigarette with a male companion in full view of the street. Golestan composed his portraits of the city’s sex workers between 1975 and 1977. “You have to remember that Golestan was a young man around 25 or 26 when he visited. I feel that, not being coy here, his drive to penetrate the space was very multi-layered,” Mahlouji says. “Many visitors to Shahr-e No went there in search of good times and absolutely loved it,” he continues, “Of course it is romanticised. Golestan’s drive is quite different. His belongs to an intellectual determination that strove to expose the marginalised characters and to motivate democratic civic action. I think the key is that the emancipation of women in the 60s created a major shift in relation to the phenomenon, which is so sensitively reflected here in the portraits by Golestan.”

|

| Kaveh Golestan ‘Prostitute’ series Photograph: Kaveh Golestan/Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

A Utopian Stage

It is this drive for cognitive reassessment and material reintegration that propels Mahlouji to decide on the subjects for his research. Aside from the archive of Golestan, a second thread of Archaeology of the Final Decade has brought to light unseen documents from the decade long Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of Arts (1967-1977). The dramatic black and white snapshots of dancers and actors preforming amongst the ancient ruins of Persepolis and in the streets of Shiraz show a cosmopolitan atmosphere of cultural efflorescence contemporary with, but worlds away from, the marginalised desolation of the capital’s red-light ghettos captured by Golestan. In a restaging of the material evidence at London’s Whitechapel Gallery this spring entitled “A Utopian Stage”, Mahlouji has not only created access to scarce images and paraphernalia of the event, but has also taken to task misconceptions and mythologies surrounding the festival itself and its original curatorial vision. Mahlouji is also writing his book Perspectives on The Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis with Black Dog Publishing due later this year.

|

| Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of the Arts Photograph: Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

|

| Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of the Arts. Courtesy The Guardian. |

Like the case of Shahr-e No, the official ban on the materials left over from Shiraz-Persepolis has exaggerated a cultural amnesia. The painstakingly reassembled archives show that performance art offerings from indigenous “third world” cultures from Africa and Asia combined with commissions from the Western European avant-garde created a cultural festival with a sophisticated and multinational curatorial vision. “The event itself is symptomatic of, as well as, a response to the universal moment that was taking place,” says Mahlouji, “the Cold War, Vietnam, decolonisation… this was also the time of avant-garde developments on both sides of the Iron Curtain”. Contemporary Iranian performance art was exposed to, and no doubt benefited from, this intercultural contact. Mahlouji believes the aim of the festival was to foster an introspective criticality about Iran’s own cultural position in the world. When asked what he thinks is most pertinent in terms of his research into the Festival as a part of his project: “Perhaps the universalism that the event proposed is its most important legacy and is indeed worth revisiting. It unified cultures not under a single globlised model but in finding common roots across differences. It also equalised cultures across the colonial juncture. No wonder the avant-gardists flocked there,” he replies.

|

| Shiraz-Persepolis Festival of the Arts Photograph: Courtesy of Vali Mahlouji and The Guardian. |

In terms of the project’s next steps, there are larger plans to digitise the archives in their entirety. “It is important that this material is kept alive for education, posterity and history,” Mahlouji concludes. Each third of Archaeology of the Final Decade is composed of the rare and compelling evidence of the cultural activity of Iran’s “lost decade”: the country’s international arts festival, its capital’s citadel of sin and the risqué experiments of one of its finest documentary photographers. Mahlouji has met many Iranians who are completely unaware of these events, spaces and images, and through his exhibitions and publications he has made it his prerogative to bring them back into both public discussion and collective memory.

- Polaroids by Kaveh Golestan, Art Dubai, 18–21 March

- Kaveh Golestan’s Prostitute series, Photo London at West Wing Embankment Gallery, Somerset House 21-24 May

- A Utopian Stage: The Archives of Festival of Arts, Shiraz Persepolis, Whitechapel Gallery in London, mid-April thru October.

Via The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment