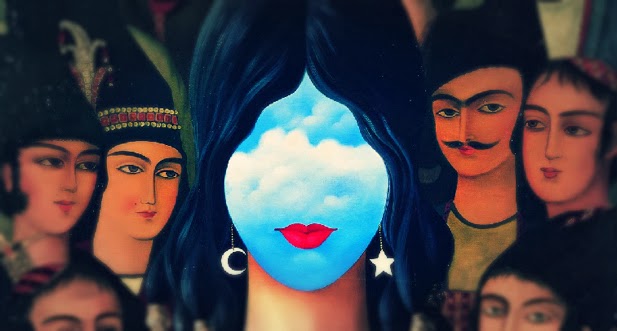

Songs of yearning, desire, and despair from the female Iranian vocal tradition

|

| Ali Akbar Sadeghi, still from Malek Khorshid (The Sun King),1975. |

REORIENT

It stands in supplication, rending its breast, crying out to the heavens above, a look of anguish on its stony, weathered face. With curiosity and awe, I regard the statue of a singing woman, unearthed from a grave in Marlik, an ancient site in the foggy, leafy, Northern Iranian province of Gilan by the Caspian Sea. Images from Ebrahim Golestan’s haunting documentary, The Hills of Marlik flash before my eyes, and for a moment, I try to imagine the story behind this, as well as the other myriad statues of men, women, and animals sculpted some 3,000-odd years ago by the roughened hands of my ancestors. And the fruits of the earth once again returned to the earth; and the earth is a woman deep in slumber, with secrets and dreams. Who was this woman, I ask myself; what was her song, and to whom was it addressed? Gazing at these earthenware sculptures, almost childlike in their simplicity and earnestness, I find myself in disbelief, tempted to look upon them as the stuff of myth and fable; but again, the images flicker before me, and I’m reminded of the reality: But they were – they ate, slept, laughed, and dreamt.

From the songs of Marlik to those of today’s generation of musicians, Iranian women have been continuing a tradition that, while suppressed at various points in Iranian history, still remains ever strong and forceful. With the fall of the Sassanian Empire and the ushering in of new traditions, the female vocal tradition was relegated more or less to haram (lit. ‘forbidden’) territory, although it nonetheless managed to survive the ravages of time, and even enjoy a popular resurgence from the early 20th century onwards. Today, efforts are yet again being made to stifle the sound of Iranian women. While a ban on solo female singing in Iran is in place, that hasn’t diminished its popularity in any respect, nor has it deterred female Iranian singers from performing, recording, and touring, albeit outside the country. If you want these bonds broken, wrote Forough Farrokhzad in a poem addressing the Iranian woman, grasp the skirt of obstinacy!

In an attempt to capture the spirit of contemporary female Iranian vocal music, Oslo-based director, producer, composer, and human rights activist Deeyah Khan has released a new compilation of songs on her Fuuse label. Entitled Iranian Woman, aptly featuring the aforementioned statue from Marlik on the cover, the album presents a well-rounded selection of contemporary and traditional sounds from both prominent and emerging female vocalists and musicians, revolving around the themes of yearning, desire, and despair – moods that are not only universal, but that are also particularly reflective of the state of the all but silenced female vocal tradition in Iran.

Spring came, but neither flowers nor roses, nor the fragrant breeze of March … Choosing Mahsa Vahdat’s Sorrowful Spring as the opening track, the story of the Iranian woman begins on a rather somber note. Accompanied by an ethereal sounding clarinet, as well as the subtle notes of the kamancheh and barbat, Vahdat (whose sister Marjan also makes an appearance on the sleepy Rooted in You) laments the coming of a spring – heralded by Norooz, the Iranian New Year – devoid of any signs of life, renewal, or rebirth. What happened to this garden, what? asks Vahdat; blood drips from the petals of flowers … where is the nightingale’s cry? The same sentiment, more or less, is also expressed on Naghmeh Gholami’s orchestral Avaz-e Sarv (Song of the Cypress), which, unlike Sorrowful Spring, more than makes up for its lyrical aura of hopelessness with its nostalgic Qajar-era instrumentation, featuring the tar and tonbak, as well as lush backing strings. Similarly, Hengam (Moment) brilliantly captures the feel and poignancy of a poem by the late Nima Yushij, one of the pioneers of the She’r-e No (lit. ‘New Poetry’) movement of the mid 20th century. Here, vocalist Raha and acclaimed multi-instrumentalist Hossein Alizadeh engage in an emotional round of call-and-response, wherein Alizadeh provides the instrumental equivalent of each and every one of Raha’s inflections. ‘Tis a silent night, all is loneliness / A man on the road plays the reed, his song sorrowful to my ears / I too am lonely … I, whose eyes unleash a torrent of tears … And, if Vahdat, Gholami, and Raha don’t make themselves clear enough, Fariba’s gutsy, heart-rending Avaz-e Dashti (Song in the ‘Dashti’ Mode) cuts – almost literally – straight to the point: I can’t see any sign of happiness; pain, sorrow, and anguish are all that remain of this wasted life.

While Iranian Woman certainly has its ‘depths of despair’, to simply look upon traditional Iranian singing (i.e. the avaz tradition) as ‘depressing’ – as many are wont to do – would be to disregard what perhaps constitutes its essence: desire and longing. Forcefully commencing the next ‘set’ of songs is Mamak Khadem’s Bigharar (Restless), with its driving rhythm and piercing tribal-flavoured melody on the zorna. O, fair beauty, my lost beloved, return, return! cries an impassioned Khadem at the chorus; I ache of loneliness, I burn of shame, I’m restless and ecstatic, O my love! On a similar note is Niyaz’s The Hunt, a rendition of a popular Khorasani folk song galvanised by Carmen Rizzo’s electronic wizardry and Azam Ali’s hypnotic vocals, as well as Sussan Deyhim’s otherworldly Parvaneh va Sham’ (The Moth and the Candle). It’s perhaps the latter that is the highlight of the collection of the more contemporary-sounding numbers, and to a degree, the entire album. Known for her soaring, ambient vocal alchemy and flair for breathing new life into staples of classical Persian poetry, The Moth and the Candle is no exception to her repertoire. Through Deyhim’s multilayered, brooding vocals, the jangly notes of the tar, and – quite tastefully – the drone of an Indian tambura, a ghazal by the medieval poet Saadi, featuring a conversation between two prominent symbols in Persian Sufi poetry is beautifully brought to life:

I remember well a restless, sleepless night,

When I heard the moth say to the candle bright:

‘I’m in love – if I burn, from blame I’m free;

Why dost thou weep and burn thus, in misery?

Said the candle, ‘O, poor friend of mine,

My sweet love’s gone, and left me behind.

Like Shirin my love fleeth from mine embrace;

Like Farhad I’m consumed by sorrow’s flame’.

The candle wailed thus; endlessly the flood of pain

The candle’s pallor of colour did drain.

Said he, ‘If love hath burned but thine wing,

Look how love’s burned my entire being!

Thou fleest from a flame raw and unscathed;

Till I’m consumed whole, I’ll standing remain’

Khadem, Ali, and Deyhim’s songs aside, the remainder of the album is largely traditional in style, form, and composition, and continues unwaveringly along the same theme of desire. On Yasna’s Atash-e Tabnak (Bright Fire), Sepideh Raissadat’s Na’reh-ye Showgh (Cry of Joy), and Pari Maleki’s Miyan-e Tariki (Amidst the Darkness), the usual roundup of instruments such as the setar, tar, santur, kamancheh, and of course, the tonbak, can be heard, as well as the recitation of classical Persian poetry, as is often the case in the avaz tradition. While Yasna opts for a poem by Hafez, replete with Zoroastrian imagery and motifs (perhaps partly owing to her pseudonym, which refers to the hymns of the Zoroastrian Avesta), and Maleki, one by Forough Farrokhzad – a rather unfitting choice, given the music – Raissadat instead sings interspersed verses from a Saadi poem, although this time the desire expressed is more earthly than divine: I could never imagine myself being with you – I can’t believe this, that it’s me sitting beside you …

That being said, however, when it comes to the album’s more traditional moments, it’s Parissa’s Masnavi that represents its zenith. Here, the acclaimed singer – perhaps the most revered of her kind, both inside and outside Iran – does away with any fancy instrumentation, save the somber notes of a sole barbat, to let her vocal prowess shine through a soulful recitation of a poem from Rumi’s Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi (The Divan of Shams of Tabriz). In terms of composition and feeling, it’s as authentic as it gets, and considering the poetry, the style couldn’t be more fitting. In an impassioned moment of fervour, her cries resounding in the void, she echoes Rumi’s lament to his beloved:

Thine visage the Kaaba of the heart, and food for the soul;

O soul of all, like a candle I’ve burned from thine sorrow whole.

Lift the veil; lift the veil and reveal thine face to thine lover,

Such that my soul’s raiment may tear and rent itself asunder!

Ever since, O soul of all, my qibla’s become thine face,

I’ve not knowledge of the Kaaba, nor of the qibla’s place.

… Worth more than a hundred worlds is but an hour of love;

A hundred lives compare not to the lover’s sacrifice, my love

Though it has been stifled, suppressed, and outlawed, the voice of the Iranian woman still resonates as boldly and beautifully as ever. Her’s is a voice of yearning, desire, and at times, despair, that has for millennia constituted a fundamental element of the Iranian soul. While today’s generation of female Iranian musicians, artists, activists – and all those who fight to make their voices heard – might seem like something of an anomaly, many would simply consider these women upholders and preservers of the spirit of Iran’s shir-zanan (lit. ‘lionesses’) of old. The tales of the harpist Azadeh, Shahrzad (a.k.a Scheherazade) the storyteller, and the warriors Gordafarid and Gordieh may all be but common lore; but as Deeyah Khan’s compilation clearly shows, the legacy of the heroines of Iran’s past continues to forcefully resound through the voice of the modern Iranian woman.

Translations: Joobin Bekhrad

Artwork: Ali Akbar Sadeghi

Via REORIENT

No comments:

Post a Comment