A new documentary tells the story of a much-loved – and loathed – iconic Iranian automobile

|

| Iman Safaei – Elahi Chap Konam (Oh God, May I Roll Over; courtesy the artist, Shirin Art Gallery and REORIENT) |

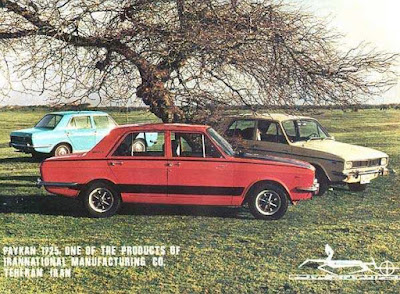

Made against all odds in a tiny studio in the heart of Tehran, Iran’s Arrow – a 75-minute documentary written, directed, produced, and edited by Shahin Armin and Sohrab Daryabandari – is the story of a car called the ‘Paykan’. Meaning ‘arrow’ in Persian, the film chronicles the social impact of the car during its lifespan on Iranians and Iran itself, both before and after the Revolution. Through a collection of interviews, recovered archival footage, film clips, photographs, and data collected from various sources, Iran’s Arrow follows the Paykan’s tumultuous path in the hands of its Iranian consumers during the four decades in which it was produced.

The Paykan – a seemingly unremarkable car – became a key figure in propelling a nation into modernity upon its production in 1967, and was later radically transformed into a symbol of resistance and endurance following the 1979 Revolution. Afterwards, it was seen as a breadwinner in times of war and distress, and ultimately became a national relic when production came to a halt in 2005. A noble and humble servant, the Paykan is an emblem hacked in Iran’s collective memory; and, to find out more about both the car and the new documentary, I chatted with Shahin and Sohrab in their Tehran studio.

Tell us a bit about the documentary. Aside from the obvious, what’s behind the choice of the title?

Sohrab – The reason we chose the title is because we thought it would point towards the trajectory of Iran in terms of how it was aiming to [progress] from a developing country to a developed [one]. [The film] also has a subtitle: The Rise and Fall of the Paykan.

For the Persian version [of the film], we called it This Paykan. I arrived at this by thinking about two things: one was the phrase, ecce homo – you know, ‘behold the man!’ I wanted to say, ‘behold the car!’ I was [also looking at] Magritte’s ‘this is not a pipe’ (The Treachery of Images), thinking, ‘this is not a car’. I mean, the movie isn’t really about a car, but it really is. [Later], I told Shahin about it, and he accepted without hesitation; this happened towards the end of the project.

|

| A 1960s advertisement for the Paykan; ; courtesy REORIENT |

What was the history of the Paykan in Iran?

Shahin – ‘Paykan’ means ‘arrow’ in Persian. [The car] was manufactured in Iran, but it was originally British, designed by the now-defunct Rootes Group. Rootes were in a bad financial position in the early 60s, and decided to design a simple car under the ‘Arrow’ name. Although the car was not a huge success in [neither] the UK nor the rest of the world, the Paykan became Iran’s most popular car for almost four decades. The production of the Paykan began in 1967, and continued until 2005.

It is quite unusual for such a car to become the subject of a documentary, especially one which, in the eyes of many (according to your film), is both famous and infamous; yet, you took it upon yourselves to go ahead with the concept. Why the Paykan?

Shahin – I had worked for 13 years in the US auto industry as a design engineer for Chrysler in Detroit, and as a product engineer at Honda. [During] all those years, I couldn’t get this freaking Paykan out of my head, and wondered what this car meant to my identity as an Iranian-American. In 2009 I decided to created a blog, and called it PaykanHunter.com. My first post on the blog was [titled] Let there be Paykan. When I uploaded that first blog post, I knew it was the beginning of something I wouldn’t be able to stop. A lot of people started to make fun of me for writing a blog about a ridiculous-looking, [little-known] car; [but], as an Iranian, I wanted to find out why we had been destined to drive it. I also believe that through cars, we can resolve a lot of misunderstandings that exist about Iran. Loving cars is a universal language, and knowing that Iranians have so much passion for them [can] paint a different picture of Iran.

|

| The good life … (a photograph of the uncle of one of Shahin’s friends taken sometime in the early 70s; courtesy PaykanHunter.com and REORIENT) |

The more I delved into the Paykan’s history, the more interested I became in its social impact on Iran’s history and Iranians throughout its long years of production. I had this dream [about] how cool it would be to see a comprehensive documentary about the Paykan, [and] had a feeling that nobody would make [such a] film except me. Now, I’ve made the film I wanted to be seen.

Why did you two decide to team up?

Sohrab – Well, I really liked how enthusiastic Shahin was about the car. The image of this car engineer sitting in his apartment in Detroit and writing a blog about this car caught my attention; I am interested in [issues of] displacement, mobility, and migration. Writing about the Paykan from Detroit in English had a special meaning for me; I thought [Shahin] had something. He used to visit me every once in a while to discuss what he was doing, and told me that he thought there should be a documentary about this car. I thought he should have made it himself and wanted to [only] help him make it, but soon after we started to work, I realised I was playing the role of a director, too.

|

| What car does Miss Iran drive? A Paykan, of course! (a Miss Iran contestant on the cover of a 1977 edition of Iran’s Zan-e Rooz (Modern Woman) magazine; courtesy REORIENT) |

Shahin – It was not until I started talking seriously with Sohrab that I became confident enough that I had collected enough material to tell a story. He was amongst the people who didn’t make fun of me; he took my research and project very seriously. He told me something that stuck in my head: ‘when there is a change, there is a story’. The Paykan changed Iran, and our film is about the story of that transformation.

In your film, you show how the Paykan was celebrated as Iran’s national car upon its production in 1967. Can you tell us why this car was seemingly chosen as the ‘national’ one to begin with?

Sohrab – As far as I know, the Paykan was never officially regarded as a ‘national’ car by any authorities; the Iranian people gave it this title. I like to think this happened after many years, and not during the first few ones. The Shah’s government did a lot of manoeuvring, but they never called it that. Technically, our national car is now Iran Khodro’s Samand (introduced in 2000), [according to] government officials; but then again, it seems the people have not accepted the Samand as their national car.

|

| A 1971 advertisement for the Paykan Kar (‘Work’ model; courtesy PaykanHunter.com and REORIENT) |

Shahin – There were government backings for the Paykan, but the most important thing is that it came out at the right time with the right price – so it became popular. Its simple mechanics and the wide dealership network that Iran National created through Iran really formed a foundation for creating and training mechanics and [producing] body shop careers. People learned the basics of car repair work with the Paykan, and now, Iran is the biggest car producer in the Middle East. It all really started with the Paykan.

In the film, the Paykan appears as a silent and humble servant, adapting to the conflicting conditions of its times from 1967 – 2005. Can you talk about how the Paykan’s character developed and transformed throughout this time?

Sohrab – The story of the Paykan can be divided into three sections: the first is when it was brought to Iran in 1967; at that point, it was like a new bride. It was a new car with up-to-date technology, and it became very popular very fast. After a while, it turned into a hard-working mule. It was abused, while [serving as] as source of income and a reliable walking stick; but, at the end of that period, people started to get tired of it. The situation had lingered for too long, and people wondered when they would see the end of [the Paykan].

|

| A 1971 advertisement for the Paykan Kar (‘Work’ model; courtesy PaykanHunter.com and REORIENT) |

‘Salar’ is another title that Iranians gave to the Paykan; it’s difficult to find a proper translation for it. If you look in the dictionary, ‘salar’ means ‘lord’ or ‘king’, as in ‘king of the road’. I think this title was [bestowed upon] it towards the end of its journey. A few years after production stopped, many Iranians looked back and started to develop nostalgic feelings towards it. I think, in the end, most people decided to [regard it] as the walking stick rather than the never-ending nightmare. Later, it found its way to the worlds of art, design, and fashion.

Shahin – The Paykan was a symbol of consumerism, the middle class, and the ‘good life’ before the Revolution. Then, the Iran-Iraq War happened, and this car became the breadwinner of many families. A lot of people turned towards ‘mosafer-keshi’ (unofficial taxi driving) with their Paykans. There is this irony in calling it ‘salar’: it doesn’t look or perform anything like a ‘king of the road’, but this relatively unknown British sedan played such an important role in Iran [nonetheless].

|

| A 1967 Paykan advertisement (courtesy PaykanHunter.com and REORIENT) |

Your investigation of what the Paykan has meant to different people in the film is interesting. Some have gone as far as personifying the car, giving it a name as if part of their family, while others have wished the car never existed. What’s going on here? Why is there this love-hate relationship towards the Paykan amongst Iranians?

Shahin – Any object that can survive for 48 years will create [such a] love-hate relationship. It was important to not only show the love and nostalgia, but also that the Paykan really had some negative [thoughts surrounding it] – e.g., the lingering feeling that it would be with us forever with its outdated technology. This was a 1960s British sedan: it wasn’t the most comfortable car out there, nor was it easy to drive; and, after being in Iran for almost four decades, Iranians started to get tired of it.

Sohrab – The relationship with this car reminds me of a very severe form of addiction. To me, it seems this car and its industry acted like a very potent drug for our economy and culture.

Can you tell me a bit about the Paykan’s role in relation to the roots of the Happy Birthday song (Tavalodet Mobarak) becoming the standard one in Iran?

Shahin – This is one of the most important stories about this car, [yet] very few people know about it. Iran’s national birthday song was created for the Paykan. This was originally the idea of a very prominent filmmaker, Mr. Kamran Shirdel, who asked the famous [composer] Anoushiravan Rohani to make the song for a Paykan advertisement. We are very proud to have [Mr. Shirdel] explain the story in our film.

Sohrab – I just want to add that unlike in many other cases, the Khayyami brothers – and probably their advertising agency, Fakopa (managed by Farhad Hormozi) – were very smart and brave to choose Mr. Shirdel for that job. I think whoever made those choices was very clever; they made an unusual choice, and it paid off. Anoushiravan Rohani was a great choice, too. He was probably the one person who should have done this.

You’ve also showed the Paykan as being the subject of contemporary art exhibitions in Tehran. What is the significance of this?

Sohrab – The Paykan has become a point of interest amongst Iranian artists for different reasons. The term ‘Paykan art’ kept popping up in our conversations. We interviewed some artists about the aesthetics of the Paykan; I expected they would be able to draw a picture of the philosophy and implications of the car’s design, but no one came up with a good analysis.

What do you mean by ‘Paykan art’?

Sohrab – Have you heard of the [term] ‘chador art’? The way I see it, that term is an insult. It means the artist has viewed the chador as a sign of backwardness, misery, and oppression, and implies the artist is trying to profit from selling this idea to western markets. The chador is just a garment; it makes no sense to depict the women who wear it as miserable or backwards. It’s twisting the chador into an offensive concept.

I think ‘Paykan art’ is a little different, even though it resembles chador art; maybe it’s not as offensive. I also believe Iran’s Arrow somehow falls in that category itself. The difference to me is that I don’t see a sense of betrayal to our cultural atmosphere in Paykan art. For me, it’s a more organic reaction to life in Iran.

Shahin – I think it’s too early to call it ‘Pakyan art’; we shouldn’t rush to call it that. We have to wait and see if it really stays in the art scene for a longer period of time. I doubt it, but let’s see what happens. I believe our film doesn’t fall under the label, as it’s not trying to tap into a trend; it’s simply trying to fill the gap. We both thought that this film was [needed]. Hopefully, it will create a foundation for this subject that others can use or get inspired by.

What were some of the challenges you faced while shooting the film?

Sohrab – The first problem was that we were single-handed, so to say. Two people had to do the job of maybe five or six. A lot of stuff tended to slip through our fingers because of this. Shahin did a great job with the production, and really worked like a tireless machine! As well, it was hard to convince people that a film about a modest car could be interesting. Most of the time, people told me I was crazy to take on this project. Even some of our own friends didn’t feel very enthusiastic about it during the first stages of our work, and we struggled to push forward. But I was happy to see that most of these people changed their minds at some point.

|

| Adel Hosseini-Nik – Untitled (courtesy the artist, Shirin Art Gallery and REORIENT) |

We also predicted some materials would be easy to obtain. We thought there would be loads of images and resources for research and use in the film, but this was not so. We could both go on for hours about how hard it was to make this film. Very small things turned into huge problems.

Shahin – Finding archival material inside Iran was difficult; archiving is vital. This is something that hasn’t been taken seriously enough in Iran – not until recently, at least. Logistics was also a major headache. Arranging interviews, convincing some people to appear in front of our cameras, and finding good locations were really a nightmare in Tehran. Tehran’s traffic and unreliable Internet [also] added lots of complications.

Where do you plan to show your film?

Shahin – We are applying to as many festivals as we can. I am really hoping that a lot of people get a chance to see this film. Hopefully Iranians will be able to dive back into their memories, future generations will learn about the past, and foreign audiences will learn a great deal about Iran and Iranians … and the Paykan, of course!

| |

|

About the Author: Nazli Ghassemi is a San Diego-based freelance writer and novelist. Her writing collaborations with artists have appeared in publications such as Artforum, Carnegie International Magazine, Elephant, Modern Painters, and Hyperallergic, amongst others. She has lived and travelled extensively in America, Europe, and the Middle East, and is the author of Desert Mojito, a novel.

Via REORIENT

No comments:

Post a Comment