The band left their homeland to pursue their artistic dream, but it came

to an end in tragedy in a New York neighbourhood. Their families then

faced a fight to bring their bodies back

|

| Yellow Dogs memorial. Courtesy Golbarg Bashi and the Guardian. |

On a bright and cold morning on 16 November 2013, a funeral procession left Brooklyn for John F Kennedy airport. A hearse carried the body of Soroush Farazmand. Behind him in a black mini van was the body of his brother Arash, who was taller.

NoorudDean Abu Ibrahim, a Brooklyn funeral director was driving the mini van. The brothers were being flown back to Tehran for burial.

At the rear of the tragic motorcade was Peymaneh Sazegari who had driven overnight from her home in Toronto as soon as she heard the terrible news.

Sazegari was a cousin, and close to Arash and Soroush’s mother Farzaneh who was in Tehran. The two were like sisters. She had spoken frequently to the brothers about making a trip to New York to visit. She was their only family living in north America, and only an eight hour drive away, at that. But plans had always fallen through.

When Sazegari did finally visit the city, it was to help make their funeral arrangements.

Through five days of stress and uncertainty, Sazegari had kept her composure. She had navigated an unfamiliar city and handled all the necessary arrangements. But when she saw the signs for JFK, she broke down into tears.

“This is the funeral procession,” she sobbed. “This is it.”

Just a few years earlier, guitarist Arash and drummer Soroush had arrived at that airport with their instruments, excited about a future in a new country.

On 11 November 2013, just after midnight, they were shot dead in their Brooklyn home along with a close friend and collaborator, Ali Eskandarian. Their killer, Ali Mohammadi Akbar Rafie, or Rafi to the others, a fellow musician and expatriate with a history of mental illness, then shot and killed himself.

The triple-murder suicide made international headlines and shocked the New York music scene where their band The Yellow Dogs was making a mark. The media descended on the gritty Brooklyn neighborhood for the sensational story: a group of young Iranian dissidents in their twenties had left their country for the promise of artistic freedom in the United States, only to be murdered in cold blood by one of their own. Back in Iran, other forces were at play, looking to manipulate the reputation of the brothers and recast the story for a domestic audience.

Meanwhile, another story developed as the family struggled to get the bodies back to Tehran. The process gives a glimpse inside the inner workings of the Islamic republic and highlights the contentious relationship it has with the diaspora - even in death.

|

| This 2012 photo shows Yellow Dogs band members, from left, Soroush Farazmand, Siavash Karampour, Arash Farazmand and Koroush “Koory” Mirzaei. Courtesy Danny Krug/AP and the Guardian. |

Growing up in a middle class neighborhood in northeast Tehran, Arash and Soroush were like twins, and their bond was strong even when they were fighting, said Golbarg Bashi, a resident New Yorker who grew up in Shiraz with the boys’ mother.

“Why are you interfering?” they would admonish their mother, Farzaneh. “We’ll sort this out between ourselves.”

They loved music, and their circle of friends in Tehran shared their passion. As a teenager Soroush was a Beatles and Animals fan and learned the electric guitar. He co-founded The Yellow Dogs with singer Siavash Karampour and bassist Koori Mirzaei. Arash learned the drums and formed another band, the Free Keys, with frontman Pooya Hosseini and bassist Arya Afshar.

The Farazmand brothers came from an artistic family whose parents were part of a cultural elite. Their father Majid Farazmand, and mother Farzaneh Shabani, are influential screenwriters. The couple has co-written seven films and a television series. Majid’s filmography stretches to productions he did in graduate school before the 1979 revolution.

The boys’ parents belong to a guild for Iranian filmmakers called the House of Cinema. The guild has regularly been shut down and its members censored over the past 35 years.

Making music is also a risky business. In Iran, the two bands had little opportunity to thrive. Musicians aren’t free to perform at public venues without government permission and English lyrics are forbidden. Rock shows are tacitly tolerated by the authorities as long as they remain underground. The Yellow Dogs played in the Tehran underground for a few years until 2009, when they were featured in Bahman Ghobadi’s acclaimed docudrama No One Knows about Persian Cats. The film exposed Iran’s underground art scene to international audiences, but also brought The Yellow Dogs unwanted attention from Iranian authorities.

Life became difficult for The Yellow Dogs. When the band received an invitation to play Austin’s annual South by Southwest music festival and were granted artists visas, band members seized the opportunity. When they arrived in the United States, they applied for political asylum and moved to Brooklyn in early 2010. They lived in a three-story Brooklyn house with manager Ali Salehezadeh in an industrial part of east Williamsburg known as Bushwick. The house became their home, practice space, and a frequent hub for parties and family-style Persian dinners. It also evolved into a base for a collective of young Iranian men who left their families and the Tehran underground behind for artistic liberation in the west.

But in New York City, struggling musicians are a dime a dozen. Still, the band seemed uniquely poised for success, especially after earning the attention of Black Keys’ guitarist Cole Alexander at South by Southwest music festival and opening for them in a performance at Webster Hall, in Manhattan.

Back in Iran, Arash and his band The Free Keys struggled. When the band got artists visas to the US the following year, their bassist was denied a passport. The artist visas were a precious opportunity so rather than wait for him to get a passport The Free Keys recruited Rafi to fill in.

When the Free Keys arrived in New York in December 2011, Arash and Soroush were reunited. But Rafi was not part of the inner circle and quickly became alienated from the group of friends. Rafi grew up in a more conservative, religious family, which may have made it more difficult for him to cope in this new environment. Band members say he was acting increasingly erratic since they arrived in New York - hopping a subway turnstile even though they were trying to stay out of trouble and secure asylum, stealing, acting sleazy towards the girls at their parties.

Rafi didn’t apply for asylum in the United States like the others and continued to live there illegally after his visa ran out.

“His personal views conflicted with our approach to our art and to the world,” the survivors later said of Rafi. Within months of moving to a new country, and after having played just three gigs, he was kicked out of the Free Keys.

In April, Arash and Hosseini moved into the east Williamsburg house. Arash joined The Yellow Dogs as a drummer.

It was new start. They were working on new music. They became close to Eskandarian, 35, an older brother figure from Dallas who lived upstairs and was working on a novel. Eskandarian, with his Bob Dylan-esque hair would sometimes sing backup vocals at Yellow Dogs gigs.

Meanwhile Rafi’s life was spiraling out of control. He showed signs of paranoid behaviour, said Bahman Kalbasi, a New York correspondent for the BBC Persian news service. Kalbasi interviewed Rafi’s sister in the aftermath of the violence, who told him that Rafi believed he was being followed and that he was receiving strange messages.

On Facebook he made death threats to Free Keys members. “Who should I shoot first?” was one of the harrowing posts. He also posted a picture of a .318 caliber assault rifle and wrote, “I’ve become a Westerner” in Farsi. He’d learn to use that kind of weapon during his military service in Iran.

On the night of the killings, he carried the assault rifle in a guitar case, and a 100 rounds of ammunition. When he reached the house on Maujer Street, he broke in through adjoining roofs.

As Rafi shot his way through the three-story house, he found Pooya Hosseini, another musician, cowering behind a coat rack. Rafi pointed the rifle to his head and ordered him to get up. As Hosseini stared down the barrel of the gun, he was struck by how purposeful Rafi looked. He knew he had just killed others in the house. Terrified, he thought only to keep him talking as long as possible.

“Why did you bring me all the way from Iran just to abandon me?” Rafi shouted in Farsi. “What happened to us?” Apart from a text message a few months earlier, Hosseini and Rafi had not spoken in over a year.

“You had a plan to bring me here and put me in a band, but you did it just to bring me here and fix me with a group of Freemasonry,” Hosseini recalled Rafi saying. For months, Rafi had been discussing conspiracy theories to friends.

When they heard the police sirens approaching, Rafi was momentarily distracted and Hosseini tackled him. The two struggled over the gun, spraying bullets into the floor and ceiling, according to the New York Times. At first, Rafi tried to drag Hosseini to the roof. But he fled there alone, where moments later, the sound of another gunshot rang out.

|

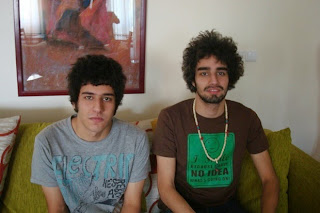

| Arash, on the right, and Soroush Farazmand. Courtesy of family and the Guardian. |

The parents of Arash and Soroush wanted their sons’ bodies sent home to them in Tehran. They felt incapable of making the arrangements from Iran and with no family in the United States they turned to a relative in Toronto - Peymaneh Sazegari, the boys’ cousin once removed. The funeral was set for the following week and the family wasn’t sure their son’s bodies would make it in time.

While in shock, Sazegari travelled south to New York, and furiously made phone calls. She felt out of her depth.

“It was only my second time in New York,” she said. “It wasn’t my city, I didn’t know anywhere. It was really hard to go around, driving, going to places and especially doing some things that are related to government permissions and things.”

Sazegari’s decision to call a Muslim funeral home came on an impulse. She said that while she and the boys’ mother believed in God, they did not seriously practice religion and the boys weren’t brought up religious either. Still, if the bodies were going to be sent back to Iran, she reasoned, it would require the proper Islamic burial rituals to be carried out beforehand.

An online search turned up NoorudDean Abu Ibrahim, a 27-year-old Palestinian-American born and raised in Brooklyn. She could not have anticipated the great support that he would give her.

“A real, real Muslim is somebody like Brother Abu,” said Sazegari. “Without him, it would have been a disaster. I like to think of him as an angel and somebody who is godsend to help us in a situation like this.”

|

| Abu Ibrahim. Courtesy John Albert and the Guardian. |

Abu Ibrahim has a full, jet-black beard, and tightly-cropped hair. In the November cold he usually wears a black leather jacket over a long black tunic. When I met him in early spring, he slipped out of a pair of black loafers to pray, revealing black business socks. Abu Ibrahim says he has been doing funeral work out of Brooklyn for nearly a decade - highly uncommon in a profession where most full-time practitioners are at least twice his age.

In his line of work, death is a normal part of everyday life. But this particular story hit him hard. The murders happened in Brooklyn, his backyard, the borough where he was born and raised. He was only two years younger than Arash, and one year younger than Soroush.

The caller ID showed an unfamiliar area code, but Abu Ibrahim is used to that. He picked up. From the other end, Sazegari asked if he shipped.

“We ship,” he said, “but I’m advising you as a Muslim brother not to.” Abu Ibrahim started ticking off the complications.

“With shipping, you’re talking about paperwork, permission letters from the consulate, health department, specialised letters, embalming…” he said. It can take days or weeks to get all the necessary affairs in order.

Abu Ibrahim also insisted to the woman that, Islamically-speaking, the dead should be buried where they die, and as fast as possible. With shipping, you contradict both of those principles, he said.

But Sazegari was adamant. The boys’ parents wanted them back.

Abu Ibrahim is Sunni. The boys, who were not religious, were born Shiite and there are differences in burial rituals. But intra-religious burial rites were the least of the problems.

The task of shipping two victims of violent crime from New York to Iran wasn’t easy. It required coordinating and filing paperwork with the medical examiner’s office and cooperating with the investigation at Brooklyn’s 90th police precinct. It meant securing a flight with all the necessary permissions from the interests section of the Islamic republic of Iran, to ensure the caskets would receive safe passage once they arrived in Iran.

And then there was the matter of payment. It would cost approximately $7,000 to send both bodies back to Iran.

Abu Ibrahim has had countless experiences shipping bodies overseas. “Usually, in cases like this when someone is killed, or murdered, or whatever, the consulate is usually quick to jump in to call,” said Abu Ibrahim. But Iranian Affairs? “Not too friendly,” he said, flatly. “Not too willing to help.

Iran doesn’t have an embassy in the US because of the strained diplomatic relations since the hostage crisis three and a half decades ago. Housed in the Pakistani embassy in Washington DC, the “Interests Section of the Islamic Republic of Iran”, as it is called, formally carries out the functions of an embassy such as passport and visa affairs. The embassy must approve all necessary paperwork from the funeral director and verify that the bodies will be received back home.

“Egypt, Morocco, when one of their people dies over here and the body needs to be shipped, they sometimes step in and say ok, we’ll cover the costs,” said Abu Ibrahim. But when he asked the Iranians whether they might be willing to help with payment, they declined.

It surprised him. The murders were a big international story and he expected the Iranian authorities would be cooperative. “This story, the murders – you just don’t hear stuff like that every day,” he said.

Abu Ibrahim reassured Sazegari that they would find another way to cover the costs. They got a break. The mosque on Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue where Abu Ibrahim conducts funeral services is just a short walk from New York State office of victim services, which provides compensation to victims of violent crimes.

Abu Ibrahim tapped into his own nonprofit, the Janazah Project, which is dedicated to helping Muslim families cover the cost of burial, to pay the expenses that were immediately due. The office of crime victims eventually reimbursed him for all the funeral and shipping costs after the Interests Section of the Islamic Republic of Iran refused. Even so, Abu Ibrahim worked practically for free to help the family.

Considering his curt treatment from Iranian Affairs, Abu Ibrahim was dumbfounded when they contacted him with a request.

No one had stepped forward to claim Rafi’s body. Would Abu Ibrahim take charge? They wanted him to handle the funeral and the shipping. They even asked whether the office of crime victims would cover the costs.

“I was bugged out,” said Abu Ibrahim. “For the ones that were innocent, I had called Iranian affairs and said we have this situation, is there anything you can do to help. And they said sorry, we don’t help in situations like this. And now they want me to do the funeral for the killer?”

When I asked him who footed the bill, Abu Ibrahim snapped back, “what, you think Crime Victims paid for it? They didn’t want anything to do with that.”

“When I got the check,” he said, “It came from Iranian affairs.”

Abu Ibrahim took the job because it was his religious duty. He wasn’t thrilled about it. But even suicide, he said, which is the gravest sin, does not take one out of the fold of Islam.

The funeral director retrieved Rafi’s body on 18 November, and suddenly, Iranian affairs was on top of things – checking to make sure Rafi’s body was picked up, the paperwork done, the flight booked.

“If they invested the same amount of help or a little bit less even, for the other two that were innocent, it would have probably felt better,” he said.

Despite their sudden attentiveness, it took ten days to arrange for Rafi’s body to be shipped. Whereas the New York police department had been extremely fast in coordinating paperwork for the victims, they took longer to organize the same paperwork for the killer.

Abu Ibrahim washed and shrouded Rafi to the best of his ability, he said, according to the book and the laws of the land. It was no different from the two brothers, although technically more complicated given the nature of the suicide – Rafi had shot himself through his chin, and the morgue had not stitched him up very well.

Although Arash and Soroush had bullet holes in their bodies, Abu Ibrahim said their washing and shrouding was simple. Saddening, but straightforward.

Abu Ibrahim would have invited the other members of the Yellow Dogs to participate in the funerals of their friends, but those survivors never met him. The same day the funeral director drove with the small motorcade transporting Arash and Souroush to JFK, the remaining members of the band were on a plane to Dallas for the funeral service of Ali Eskandarian.

John Albert is a writer and a musician based in New York City. He is a graduate of the Columbia University School of Journalism.

Via Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment