Snapshots from Tehran's contemporary art scene

In the heart of Tehran, a Moloch of 15 million people, visitors can make an astonishing discovery. In the little park in the middle of the capital, which also contains the exhibition center of the Iranian artists organization, is a small sculpture garden. Many of the statues resemble the European Modernism of the 1950s and 1960s and one might expect them to be frowned upon. Perhaps that’s why some of them have been stolen. The mysterious robbery of monuments in the middle of the Iranian capital has not been solved to this day. By contrast, statues made of barbed wire and steel helmets stand untouched on one floor of the neighboring Shohada Museum, which exhibits the legacy of the Iranian soldiers who fell in the Iran-Iraq War.

At the same time, about two kilometers away as the crow flies, the unique art collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, founded in 1975 by former Iranian Empress Farah Diba, gathers dust in Tehrnan’s Laleh Park, under the vigilant eyes of the religious leaders Ayatollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei. Under a picture by Claes Oldenburg in a yellowing Plexiglas frame, Iranian experts have turned the name of the American painter of Dutch descent into a German one: Klaus Oldenberg. The anti-American mural on the wall of the former US Embassy, by contrast, is regularly freshened up. The tour with gaps and the museum in a Sleeping Beauty slumber underscore the ambivalences of Modernism in Iran, a country between a journey toward art and iconoclasm.

So it is surprising that gallery tours are an institution every Friday afternoon in Tehran. The government suppresses every form of informal (oppositional) public realm. But in the environs of about 20 of the more than 50 galleries in Tehran, this kind of microcosm has meanwhile crystallized, borne mostly by the bourgeois middle class. Except for at the Azad Gallery of video artist Rozitha Sharafjahan, who was born in 1962 and is rooted in the left-feminist movement of the 1980s, (upper) middle-class women set the tone: for example, Nazila Noebashari with the Aaran Art Gallery and Afarin Neyssari with the Aun Gallery. In Tehran’s diplomatic quarter, Lili Golestan, who was born in 1944 and studied Decorative Arts in Paris, heads the Golestan Gallery.

They all have gathered experience in exhibiting critical art without coming into conflicts all too great with the censorship authorities at the Ministry for Islamic Guidance. When Afarin Neyssari says, "One has to defend one’s artists," this is not meant solely symbolically, but also thoroughly practically. In Iran, Tehran gallerists, who have to wait for years for their licenses and must have each exhibition approved weeks in advance, seem like pioneers of civil society: they constantly shift the boundaries of the permitted, millimeters at a time.

Six artists representatively demonstrate the precarious predicament of Iranian art in the context of a Modernism that Reza Shah Pahlavi, the father of the Shah toppled by Khomeini, brutally dictated in 1925; which then reached an initial zenith in 1958 at the beginning of the Tehran Biennial; and which the Islamic Revolution of 1979 then equally brutally revoked. Politics, identity, and the critique of masculinity are the themes that unite the generation born between 1970 and 1980 and found in these galleries.

Iman Afsarian (* 1974) takes one of the most radical positions, the thesis that there has been no Iranian art since the tradition of Persian miniatures. He sees his country’s contemporary art as a mere "copy of Western art". The artist, who leads a withdrawn life and, like many of his colleagues, also works as a critic and lecturer, explicitly includes himself in this dilemma. Perhaps that is why the classical realistic pictures in which he captures Tehran before globalization have grown so melancholy: vanished buildings, small workshops, nostalgia-suffused interiors, moments of intimacy reminiscent of Pierre Bonnard, and kitsch objects from the households of simple people.

In his aversion to the (Arab) art market and in his taste preferences, he is congruent with Barbad Golshiri (* 1982). The son of Iran’s most famous modern writer, Houshang Golshiri, who in 1994 initiated the "Appeal of the 134: We are Writers", is the political and theoretical head of his generation. Barbad Golshiri vehemently criticizes the term "Middle East" and its application to art. He considers it a strategic measure of the West, a relict of colonialism and of US global strategy. He says the term’s only purpose is to stigmatize the region as the "dark side of the world" and its "anus" and that it says as little as the generalization "the West". He rebukes artists like Shirin Neshat for "self-exoticization" and for "aestheticizing" symbols of oppression, like the chador.

The artistic spectrum of charismatic Barbad Golshiri, a rare case of a male artist who calls himself a "feminist", ranges from photography through sculptures and installations to visual poetry. But he is also an art theoretician and a translator. In 2003, an essay of his won third prize at the Tehran Biennial of the Museum for Contemporary Art. Golshiri has exhibited in London and Paris. In 2009, in the framework of the exhibition "Medium Religion" at the Center for Art and Media Technology in Karlsruhe, he exhibited his work mΛmı, a video installation that used the means of media to address the political functionalization of religion.

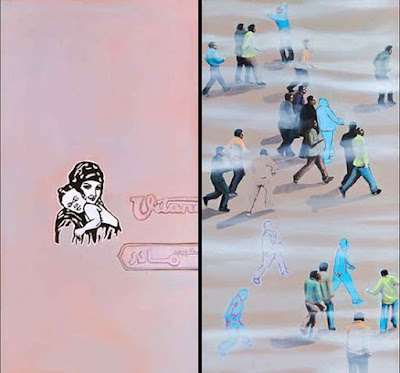

Feminism is a provocative word in Iran; that the regime prohibits its use is already reason enough for many intellectuals to profess it. But this is not the only reason why the critique of masculinity is widespread, especially among heterosexual men. The pictures of Behrang Samadzadegan, who was born in 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution, and who co-edits the alternative online magazine Tehran Avenue, are an homage to the emancipatory struggle of his mother’s generation.

In the art of the painter Shahpour Pouyan (* 1979), symbols like the tower as phallus repeatedly stand for the struggle with the power wielded by men. At the end of 2010, he showed the series "Hooves" in Gallery 66 in Tehran. A traditional religious head covering crowned the chopped-off hoof of an animal. Puyan thereby alludes to the motif of armed animals in the miniatures of the 15th-century Persian painter Siyah Qalam. But his critique of the violence of the theocracy, which gleams at the top and kicks all below it, is unmistakable.

Simin Keramati (* 1970) embodies an explicit antithesis to nostalgic, retrospectively oriented artists like Iman Afsarian. Keramati indignantly rejects any orientation toward "traditional" models. Like the video artist and painter Negar Tahsili (* 1980), she combines painting with video and film. She addresses the political struggles that she, as a lecturer at the University of Tehran, personally experienced in the year of protests against the "reelection" of President Ahmadinedjad. Her video peace "Insomnia" from the year 2010 shows nothing but a gently blowing curtain: an impressive emblem of "movement" that does entirely without blatant reference to the current political events, and yet also suggests that the political movement may come to nothing.

Womanly perspective and body experience are in the foreground with Tahsili. She presented her documentary film "Wee-Men or Women" about female Tehran taxi drivers and self-defense courses for women in 2009 in Berlin. The Tehran art scholar Hamid Keshmirshekan, editor-in-chief of the art magazine Art Tomorrow, which was newly founded in Spring 2010, sees the goal of "contemporaneity for all" behind such works. The turn to the new media expresses the artist’s wish to place his art universally, and not merely geographically.

Keramati’s most recent series of oil paintings, Blood Fever, repeats the motif found with many artists: blood running out of a nose. This characteristic symbol is especially conspicuous in the works of Masoumeh Mozaffari (* 1958). In the exhibition Heat Stroke at the end of October 2010 in the Azad Gallery, the painter showed realistic portraits of ordinary people from Tehran, all of whom have the characteristic bloody spot on their cheeks. The paintings, rendered with explicit reference to Gustave Courbet, do not make them look like injuries inflicted from the outside. Rather, the wound seems to come from inside. "It’s all about transformation," explains the gallerist Rozitha Sharafjahan ambiguously. She too criticizes contemporary Iranian art’s orientation toward short-lived, garish fashions inspired by the West. Mozaffari’s art is more to her taste. For Sharafjahan, Iranian art is "calm, monotonous, uniform, turned inward".

Six coincidental positions that are nevertheless significant: the conspicuous trademark of this generation of artists is the unconditional will to remain in Iran. The great silent march of the Green Movement in Summer 2009 nourished its hope for a radical change. It prefers the bracing political-intellectual climate of its country to that of the saturated West. "I like these conflicts. I can’t live in any other country," says Negar Tahsili, almost enthusiastically. Barbad Golshiri recently summed up this stance between lack of illusion and cheerful self-assertion under the most adverse conditions with the formulation, not without pathos, "We have decided to breathe hate, tears, and CS gas instead of clinging to nostalgic dreams, the myths of exile, or the idea of the innocent artist."

Ingo Arend

Studied politics, history and journalism. Works as a cultural journalist and essayist in Berlin since 1990.

Empty sculpture pedestal at Khane Honarmandan Park, Tehran, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran, Entrance area, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Vernissage at Aaran Gallery, October 2010, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Nazila Noebashari, Aaran Gallery, Tehran, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Afarin Neyssari, Director of Aun Gallery, Tehran, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Iman Afsarian, In his studio in Tehran, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Iman Afsarian, Untitled. 2007, Oil on canvas, Photo: Courtesy of Iman Afsarian

Imam Afsarian:1975 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

Barbad Golshiri, The Distribution of the Sacred System, Performance at Verso Artecontemporanea, Turin, Italy, 2010, Photo: Courtesy of Olka Hedayat

Barbad Golshiri: 1982 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

Behrang Samadzadegan, The painter and journalist in Tehran 2010, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Behrang Samadzadegan: 1979 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

Shahpour Pouyan, Courtesy of Ali Bhaktiari

Shahpour Pouyan, The Hoof. 2010, Acrylic on canvas, Photos: Courtesy of Shahpour Pouyan

Shahpour Pouyan: 1979 Isfahan, Iran. Lives in Tehran, Iran.

Simin Keramati: 1970 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

Negar Tahsili, Autonomy of an Iranian. 2010, Oil on canvas, Photo: Courtesy of Negar Tahsili

Negar Tahsili: 1980 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

Galerist Rozita Sharafjahan in front of works by Masoumeh Mozzafari, from the series "Heat Stroke", oil on canvas, 2010, Photo: Courtesy of Ingo Arend

Masoumeh Mozaffari: 1958 Tehran, Iran; lives there.

No comments:

Post a Comment